Why Great Ideas Fail

By Laura Hilty, HealthX Principal

Why Great Ideas Fail: The Problem Isn’t the Solution—It’s the Problem

In startups, we love to chase solutions. A shiny interface, an AI engine, or a clever new workflow promises to fix inefficiencies or transform patient care. But time and again, great ideas stumble—not because the solution wasn’t clever, but because the problem wasn’t fully understood.

Einstein famously said that if he had an hour to solve a problem, he would spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and only five minutes thinking about solutions. That mindset is just as critical for today’s innovators. Without clarity on the true nature of the problem—and for whom it exists—solutions risk being irrelevant, poorly adopted, or fatally flawed.

The Problem with Problems

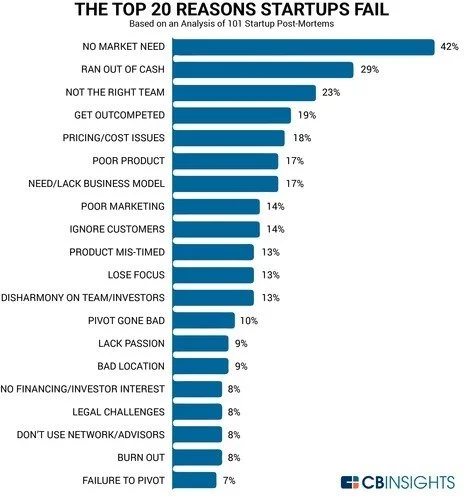

Failure data backs this up. According to CB Insights, the leading reasons startups fail cluster around one theme: a lack of true problem understanding. The very top reason for start-up failure, even ahead of “run out of cash” (which arguably is the ultimate end reason for start-up failure), is No Market Need. In other words, customers didn’t care enough about the problem the product solved, or the problem was misdiagnosed in the first place. To find true Product / Market Fit, you need to nail the Market.

Start-ups are hard. 90% of all start-ups fail, and even 30% of start-ups fail after Series C funding. But failure is not only reserved for start-ups, so let’s take an example that you may know of (depending on your age!).

Take Kodak. At its peak, it was a $16 billion company, and by far the leader of photography businesses. But Kodak misunderstood the problem it was solving. Leaders believed Kodak was in the film business, when in reality, it was in the memory-preservation business. They even invented the digital camera, but by clinging to film and their successful printing business, they missed digital photography—the actual evolution of the problem customers wanted solved—and collapsed into bankruptcy. No company is immune to failure or above the need to deeply understand their customers’ evolving needs.

After reviewing 2,000 start-ups per year and seeing the fate of those we passed investing in (and of course those we invested in), as well as having launched seven software products from ‘0 to 1’, I have a perspective beyond the statistics on what makes companies and even the greatest of ideas fail.

I believe the difference in those who succeed comes down to attitude, perspective, and a deep curiosity.

Myopia and Over-Simplification

Two of the most common traps in problem definition are:

Myopia: Startups see only what is directly in front of them. For example, they optimize for short-term revenue or a pilot win without recognizing broader system needs. This is especially risky in healthcare, where the buyer (pharma, payers, health systems) is often different from the user (patients, caregivers, clinicians). Without a 360° view, solutions can miss critical adoption drivers.

Over-simplification: While we want to make products simple to use for our end-users, often solutions get watered down because we over-simplify the problem before we start solving for it. Healthcare in particular is messy, and constantly changing. So many stakeholders with sometimes competing priorities and incentives are all at play, and if we don’t understand the depths it is all to easy to miss the mark.

Myopia can sometimes be useful. Myopia is like a racehorse with blinders on so they only are focused on what is right in front of them while the rider who has the full view, guides them. In the right contexts this is useful. Kodak likely empowered the Printing division executive(s) to have laser focus on that business line’s performance, and that was important to help them achieve $16B. However, someone needs to be like the rider who sees the full view and what is ahead. It’s critical to not get stuck in the racehorse’s view.

In another smaller division of Kodak, innovators recognized digital photography as the next wave coming, and attempted to pitch to corporate executives with what ended up being too little too late in terms of support. They missed that customers were trying to solve for the problem of easily sharing photos with loved ones, and digital opened up an entirely new world for that. The allure of immediate revenue combined with Myopia and not fully understanding or respecting customers’ problems ended up in their demise.

Listening Is the Cure

So, how do we avoid these pitfalls? We must listen widely and deeply. That means:

In healthcare, not just one patient focus group, not just not just one Key Opinion Leader (KOL) physician, but also caregivers, nurses, administrators, and site staff.

Not just your internal subject matter experts, but outside observers who see different angles

Get creative with your ‘Design Partner’ customers, don’t design for just one perspective but you need close early adopter customers by your side to be your guide

It also means being humble enough to be ruthlessly curious about your potential customers, their problems, their market. Humble enough to listen when the discoveries are the antithesis of what you had believed. The conviction to keep discovering until you hit on ‘gold’ of a deep problem that is urgent, pervasive, and unsolved.

The companies that win are those that obsess over identifying and defining the million-dollar problem before racing to the million-dollar solution.

As innovators, we should ask relentlessly:

Who truly experiences this problem?

What hidden burdens are being overlooked?

How does this problem evolve over time?

Where might our assumptions be wrong?

Great ideas don’t fail because they lack brilliance. They fail because brilliance was applied to the wrong problem or to only part of a problem. Whether you’re launching a startup, evaluating an investment, or leading a large enterprise team, your greatest leverage point is not the solution you build—it’s the problem you choose to solve, and how deeply you understand it.

So, before you design, code, or pitch—pause. Listen. Observe. Map out every nuance. Because if you get the problem right, while I won’t claim it will be easy, it will be much smoother and more impactful to the world.